This objection, as stated in the first Dubia of the four Cardinals, is that it is not:

“[P]ossible to grant absolution in the sacrament of penance, and thus to admit to holy Communion a person who, while bound by a valid marital bond, lives together with a different person more uxorio without fulfilling the conditions provided for by Familiaris Consortio 84, and subsequently reaffirmed by Reconciliatio et Paenitentia 34 and Sacramentum Caritatis 29“.

1.1 Doctrinal Background of the Objection

The impediment to the D&R not living in complete continence receiving Holy Communion, referred to in this objection, is expressed in the discipline of the Church by Canon 916:

“A person who is conscious of grave sin is not to … receive the body of the Lord without previous sacramental confession”.

As made clear in CCC 1385, this law expresses the doctrinal truth taught by St Paul in 1 Corinthians 11:27-31:

“Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord. Let a man examine himself, and so eat of the bread and drink of the cup. For anyone who eats and drinks without discerning the body eats and drinks judgment upon himself. That is why many of you are weak and ill, and some have died. But if we judged ourselves truly, we should not be judged. But when we are judged by the Lord, we are chastened so that we may not be condemned along with the world”.

The impediment for these same people from obtaining sacramental absolution, referred to in this objection, is expressed in Chapter 4 of the 14th Session of the Council of Trent (quoted by CCC 1451):

“Contrition, which holds the first place amongst the aforesaid acts of the penitent, is a sorrow of mind, and a detestation for sin committed, with the purpose of not sinning for the future. This movement of contrition was at all times necessary for obtaining the pardon of sins; and, in one who has fallen after baptism, it then at length prepares for the remissions of sins, when it is united with confidence in the divine mercy, and with the desire of performing the other things which are required for rightly receiving this sacrament”.

Further, as confirmed in Canon 22 of the Second Lateran Council, all relevant sins are required to be confessed in order to obtain sacramental absolution:

“[T[here is one thing that conspicuously causes great disturbance to holy church, namely, false penance, we warn our brothers in the episcopate and priests not to allow the souls of the laity to be deceived or dragged off to hell by false penances. It is agreed that a penance is false when many sins are disregarded and a penance is performed for one only, or when it is done for one sin in such a way that the penitent does not renounce another. Thus it is written: Whoever keeps the whole law but fails in one point, has become guilty of all of it; this evidently pertains to eternal life”.

1.2 Teaching of AL

This objection arises because AL teaches that there are circumstances where it is possible to admit the D&R not living in complete continence to the Sacraments of Penance and Holy Communion.

The sections of AL which do this are summarised by the Buenos Aires Directive, in relation to which Pope Francis has confirmed:

“The document is very good and completely explains the meaning of chapter VIII of Amoris Laetitia. There are no other interpretations”.

The Buenos Aires Directive provides that:

“If one arrives at the recognition that, in a particular case, there are limitations that diminish responsibility and culpability (cf. 301-302), particularly when a person judges that he would fall into a subsequent fault by damaging the children of the new union, Amoris Laetitia opens up the possibility of access to the sacraments of Reconciliation and the Eucharist (cf. notes 336 and 351)”.

These footnotes, being 336 and 351, demonstrate that the basis for the possibility of access to the Sacraments is reduced culpability. Footnote 336 forms part of AL 300, which states:

“What is possible is simply a renewed encouragement to undertake a responsible personal and pastoral discernment of particular cases, one which would recognize that, since “the degree of responsibility is not equal in all cases”, the consequences or effects of a rule need not necessarily always be the same”.

Footnote 336 itself then goes on to state:

“This is also the case with regard to sacramental discipline, since discernment can recognize that in a particular situation no grave fault exists. In such cases, what is found in another document applies: cf. Evangelii Gaudium (24 November 2013), 44 and 47”.

EG 44, referred to in this footnote, provides “pastors … must always remember” what CCC 1735 “teaches quite clearly”. In this regard CCC 1735 states:

“Imputability and responsibility for an action can be diminished or even nullified by ignorance, inadvertence, duress, fear, habit, inordinate attachments, and other psychological or social factors”.

This reference to CCC 1735 is further reinforced in AL 302, which quotes it as well as CCC 2352, to confirm that:

“[A] negative judgment about an objective situation does not imply a judgment about the imputability or culpability of the person involved”.

In this regard, CCC 2352 states:

“To form an equitable judgment about the subjects’ moral responsibility and to guide pastoral action, one must take into account the affective immaturity, force of acquired habit, conditions of anxiety or other psychological or social factors that lessen, if not even reduce to a minimum, moral culpability”.

AL 302, in Footnotes 344, 345 and 346, also refers to the following precedents in respect of reduced culpability:

- RP 17.

- Declaration on Euthanasia II.

- 2015 Relatio Finalis 85.

- 2000 PCLT Declaration 2 a).

Similarly, Footnote 351 forms part of AL 305, which states:

“Because of forms of conditioning and mitigating factors, it is possible that in an objective situation of sin – which may not be subjectively culpable, or fully such – a person can be living in God’s grace, can love and can also grow in the life of grace and charity, while receiving the Church’s help to this end.”

Footnote 351 itself then goes on to state “In certain cases, this can include the help of the sacraments”.

1.3 Reduced Culpability and Mortal Sin

The relevance of reduced culpability for access to the Sacraments is its relationship to the distinction between mortal and venial sin. For a sin to be mortal, rather than venial, CCC 1857-1860 provides three conditions must together be met:

““Mortal sin is sin whose object is grave matter and which is also committed with full knowledge and deliberate consent.” …

Grave matter is specified by the Ten Commandments, corresponding to the answer of Jesus to the rich young man … Do not commit adultery …

Mortal sin requires full knowledge and complete consent. It presupposes knowledge of the sinful character of the act, of its opposition to God’s law. It also implies a consent sufficiently deliberate to be a personal choice. Feigned ignorance and hardness of heart do not diminish, but rather increase, the voluntary character of a sin …

Unintentional ignorance can diminish or even remove the imputability of a grave offense. But no one is deemed to be ignorant of the principles of the moral law, which are written in the conscience of every man. The promptings of feelings and passions can also diminish the voluntary and free character of the offense, as can external pressures or pathological disorders. Sin committed through malice, by deliberate choice of evil, is the gravest”.

In this regard, as outlined by RP 17, objective grave sin and subjective mortal sin are sometimes conflated in practice:

“Considering sin from the point of view of its matter, the ideas of death, of radical rupture with God, the supreme good, of deviation from the path that leads to God or interruption of the journey toward him (which are all ways of defining mortal sin) are linked with the idea of the gravity of sin’s objective content. Hence, in the church’s doctrine and pastoral action, grave sin is in practice identified with mortal sin”.

However, as recognised by VS 70 and RP 17 in light of the Council of Trent, they are not in fact the same:

“The Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Reconciliatio et Paenitentia reaffirmed the importance and permanent validity of the distinction between mortal and venial sins, in accordance with the Church’s tradition. And the 1983 Synod of Bishops … “not only reaffirmed the teaching of the Council of Trent concerning the existence and nature of mortal and venial sins, but it also recalled that mortal sin is sin whose object is grave matter and which is also committed with full knowledge and deliberate consent“.

The statement of the Council of Trent does not only consider the “grave matter” of mortal sin; it also recalls that its necessary condition is “full awareness and deliberate consent”. In any event, both in moral theology and in pastoral practice one is familiar with cases in which an act which is grave by reason of its matter does not constitute a mortal sin because of a lack of full awareness or deliberate consent on the part of the person performing it”.

As noted above, CCC 1735 and 2352 provide examples of the factors which can limit full knowledge and complete consent, and thus reduce subjective culpability for an objectively grave sin from mortal to venial. For instance these can be limited by:

- Full knowledge – Ignorance or inadvertence.

- Full consent – Duress, fear, habit, inordinate attachments, affective immaturity, conditions of anxiety or other psychological and social factors.

The principle that reduced subjective culpability can render all objective grave sins (even those intrinsically evil) subjectively venial was confirmed by Pope St John Paul II on a number of occasions, including:

- Canon 1324 – “The perpetrator of a violation is not exempt from a penalty, but the penalty established by law or precept must be tempered or a penance employed in its place if the delict was committed … by a person who was coerced by grave fear, even if only relatively grave, or due to necessity or grave inconvenience if the delict is intrinsically evil or tends to the harm of souls”.

- RP 16 and 17 – “This individual may be conditioned, incited and influenced by numerous and powerful external factors. He may also be subjected to tendencies, defects and habits linked with his personal condition. In not a few cases such external and internal factors may attenuate, to a greater or lesser degree, the person’s freedom and therefore his responsibility and guilt … [T]here exist acts which, per se and in themselves, independently of circumstances, are always seriously wrong by reason of their object. These acts, if carried out with sufficient awareness and freedom, are always gravely sinful … Clearly there can occur situations which are very complex and obscure from a psychological viewpoint and which have an influence on the sinner’s subjective culpability”.

- CCC 1754 – “The circumstances, including the consequences, are secondary elements of a moral act. They contribute to increasing or diminishing the moral goodness or evil of human acts (for example, the amount of a theft). They can also diminish or increase the agent’s responsibility (such as acting out of a fear of death). Circumstances of themselves cannot change the moral quality of acts themselves; they can make neither good nor right an action that is in itself evil”.

- VS 63 and 81 – “It is possible that the evil done as the result of invincible ignorance or a non-culpable error of judgment may not be imputable to the agent; but even in this case it does not cease to be an evil, a disorder in relation to the truth about the good … If acts are intrinsically evil, a good intention or particular circumstances can diminish their evil, but they cannot remove it”.

- EE 37 – “The judgment of one’s state of grace obviously belongs only to the person involved, since it is a question of examining one’s conscience.”

These confirmations are based on the traditional moral theology of the Church, which provides that subjective factors which render an act less than voluntary such as invincible ignorance and a lack of consent can reduce culpability, as seen in:

- St Thomas Aquinas in his ST I-II, q.6 and ST I-II, q. 19.

- Pope Alexander VIII in his Decree on Jansenists.

- St Alphonsus Liguori in his TM Lib. 1; Tract. 1; Cap. 1; n.1-7 and Sermon XLVII.

For example St Alphonsus Liguori, in his Sermon XLVII, taught:

“It is not the bad thought, but the consent to it, that is sinful. All the malice of mortal sin consists in a bad will, in giving to a sin a perfect consent, with full advertence to the malice of the sin. Hence St. Augustine teaches, that where there is no consent there can be no sin … (De Vera Eel, cap. xiv.) Though the temptation, the rebellion of the senses, or the evil motion of the inferior parts, should be very violent, there is no sin, as long as there is no consent. ” Non nocet sensus,” says St. Bernard, “ubi non est consensus.” (De Inter. Domo., cap. xix.)”.

Similarly, the ability of grave fear and necessity to reduce culpability for intrinsic evils, was taught for example by Canon 2205 of the 1917 CCL:

“Grave fear, even relatively such, necessity and also great inconvenience, excuse as a rule from all guilt, if there is question of purely ecclesiastical laws … If, however, the act is intrinsically evil, or involves contempt of faith or of ecclesiastical authority, or the harm of souls, the circumstances spoken of in the preceding paragraph do indeed diminish the responsibility but do not take it away”.

The application of these principles to sins of a sexual nature is well established. For example the CDF, in 1975, stated in Persona Humana at 10:

“It is true that in sins of the sexual order, in view of their kind and their causes, it more easily happens that free consent is not fully given; this is a fact which calls for caution in all judgment as to the subject’s responsibility. In this matter it is particularly opportune to recall the following words of Scripture: “Man looks at appearances but God looks at the heart.” However, although prudence is recommended in judging the subjective seriousness of a particular sinful act, it in no way follows that one can hold the view that in the sexual field mortal sins are not committed”.

Further, the application of this principle to the D&R was confirmed under Pope St John Paul II in the 2000 PCLT Declaration, which stated that:

“[T]o establish the presence of all the conditions required for the existence of mortal sin, including those which are subjective, necessitating a judgment of a type that a minister of Communion could not make ab externo …

[B]eing that the minister of Communion would not be able to judge from subjective imputability”.

That this declaration does indeed apply the principle of reduced culpability to the D&R was further confirmed by the then Cardinal Ratzinger (now Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI) in his 2004 CDF Memo at 7:

“When “these precautionary measures have not had their effect or in which they were not possible,” and the person in question, with obstinate persistence, still presents himself to receive the Holy Eucharist, “the minister of Holy Communion must refuse to distribute it” (cf. Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts Declaration “Holy Communion and Divorced, Civilly Remarried Catholics” [2002], nos. 3-4). This decision, properly speaking, is not a sanction or a penalty. Nor is the minister of Holy Communion passing judgment on the person’s subjective guilt, but rather is reacting to the person’s public unworthiness to receive Holy Communion due to an objective situation of sin”.

Indeed this fact is also acknowledged in the notes to the third Dubia of the four Cardinals:

“In its “Declaration,” of June 24, 2000, the Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts seeks to clarify Canon 915 of the Code of Canon Law, which states that those who “obstinately persist in manifest grave sin are not to be admitted to holy Communion.” The Pontifical Council’s “Declaration” argues that this canon is applicable also to faithful who are divorced and civilly remarried. It spells out that “grave sin” has to be understood objectively, given that the minister of the Eucharist has no means of judging another person’s subjective imputability.

Thus, for the “Declaration,” the question of the admission to the sacraments is about judging a person’s objective life situation and not about judging that this person is in a state of mortal sin. Indeed, subjectively he or she may not be fully imputable or not be imputable at all …

Hence, the distinction referred to by Amoris Laetitia between the subjective situation of mortal sin and the objective situation of grave sin is indeed well established in the Church’s teaching”.

Further, prior to AL, the Church also taught that reduced culpability can render other objectively grave sins venial rather than mortal, including same sex relations, abortion, suicide, euthanasia and artificial contraception. The precedents in relation to these sins are separately considered by this Apologia at 7.0 Slippery Slope, particularly at 7.2 Reduced Culpability and Canon 916.

1.4 Internal Forum and Nullity

AL provides a number of examples of different circumstances the D&R may find themselves in, which must be adequately distinguished by a careful discernment. One of the examples noted by AL, quoting FC 84, is where a person is subjectively certain in conscience their first marriage was never valid (AL 298):

“The divorced who have entered a new union, for example, can find themselves in a variety of situations, which should not be pigeonholed or fit into overly rigid classifications leaving no room for a suitable personal and pastoral discernment … There are also the cases … “those who have entered into a second union for the sake of the children’s upbringing, and are sometimes subjectively certain in conscience that their previous and irreparably broken marriage had never been valid””.

The need to “exercise careful discernment of situations” and a recognition that “[t]here is in fact a difference” in these circumstances was already acknowledged by FC 84.

The basis for this difference is that while “no one is deemed to be ignorant of the principles of the moral law, which are written in the conscience of every man” (CCC 1860) such as the Sixth Commandment that “You shall not commit adultery”, a conscience which errs or is ignorant of the validity of a marriage, does not mortally sin due to a lack of full knowledge. As noted by St Thomas Aquinas in his ST I-II, q. 19, a. 6:

“For instance, if erring reason tell a man that he should go to another man’s wife, the will that abides by that erring reason is evil; since this error arises from ignorance of the Divine Law, which he is bound to know. But if a man’s reason, errs in mistaking another for his wife, and if he wish to give her her right when she asks for it, his will is excused from being evil: because this error arises from ignorance of a circumstance, which ignorance excuses, and causes the act to be involuntary”.

Accordingly, even if one who is subjective certainty of nullity is objectively wrong, it maybe they are inculpably ignorant as to the fact they are married. As such subjective certainty of nullity is merely an example of reduced culpability due to a lack of full knowledge, as outlined above at 1.2 and 1.3.

Further while it may be thought such ignorance could be cured by the processes of the Church in the external forum, such as its marriage tribunals, Canon 1060 provides that:

“Marriage possesses the favour of law; therefore, in a case of doubt, the validity of a marriage must be upheld until the contrary is proven”.

Accordingly, while a declaration of nullity may not be able to be provided by the Church due for example to insufficient evidence being available to prove nullity, a person’s own knowledge may be sufficient for them in conscience to be certain of nullity.

It may be objected that even if a first marriage was invalid such that a subsequent civil marriage is not adultery, without a declaration of nullity objectively it will still be the sin of fornication, a “carnal union between an unmarried man and an unmarried woman” (CCC 2353).

This arises because of the “canonical form” requirement in Canon 1108, which provides that “Only those marriages are valid which are contracted … according to the rules expressed in the following canons”, such that a civil marriage by a Catholic outside the Church is invalid rather than just illicit.

However this invalidity is not a doctrinal requirement nor part of divine law, as shown by the fact that it does not apply to baptised non-Catholics, as provided by Canon 1117:

“The form established above must be observed if at least one of the parties contracting marriage was baptized in the Catholic Church or received into it and has not defected from it by a formal act”.

This can also be seen in Chapter 1 of the Decree Concerning The Reform Of Matrimony of the 24th Session of the Council of Trent, which introduced the rules of canonical form represented by Canon 1108:

“Although it is not to be doubted that clandestine marriages made with the free consent of the contracting parties are valid and true marriages so long as the Church has not declared them invalid, and … the holy council does condemn them with anathema, who deny that they are true and valid … nevertheless the holy Church of God has for very just reasons at all times detested and forbidden them. But while the holy council recognizes that by reason of man’s disobedience those prohibitions are no longer of any avail, and considers the grave sins which arise from clandestine marriages, especially the sins of those who continue in the state of damnation, when having left the first wife with whom they contracted secretly, they publicly marry another and live with her in continual adultery, and since the Church which does not judge what is hidden, cannot correct this evil unless a more efficacious remedy is applied, therefore … Those who shall attempt to contract marriage otherwise than in the presence of the parish priest or of another priest authorized by the parish priest or by the ordinary and in the presence of two or three witnesses, the holy council renders absolutely incapable of thus contracting marriage and declares such contracts invalid and null, as by the present decree it invalidates and annuls them”.

This passage from the Council of Trent also shows that canonical form was not introduced with the intent that it would apply to the subsequent civil marriages of those who are subjectively certain of the nullity of their first marriage.

Accordingly it may be that the application of canonical form to these cases is able to be set aside under the canonical concept of “epikeia” or “aequitas canonica”. St Thomas Aquinas explains in relation to epikeia that (ST II-II, q. 120, a. 1):

“[W]hen we were treating of laws, since human actions, with which laws are concerned, are composed of contingent singulars and are innumerable in their diversity, it was not possible to lay down rules of law that would apply to every single case. Legislators in framing laws attend to what commonly happens: although if the law be applied to certain cases it will frustrate the equality of justice and be injurious to the common good, which the law has in view … On these and like cases it is bad to follow the law, and it is good to set aside the letter of the law and to follow the dictates of justice and the common good. This is the object of “epikeia” which we call equity”.

In this regard the application of the concept of epikeia / aequitas canonica is restricted to ecclesiastical, rather than divine, laws as noted by the then Cardinal Ratzinger (now Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI) in his 1998 CDF Memo at 3:

“Epikeia and aequitas canonica exist in the sphere of human and purely ecclesiastical norms of great significance, but cannot be applied to those norms over which the Church has no discretionary authority. The indissoluble nature of marriage is one of these norms which goes back to Christ Himself and is thus identified as a norm of divine law”.

This does not however prevent its application to canonical form, which as demonstrated above, is not to be identified as a norm of divine law.

Accordingly, based on the application of epikeia / aequitas canonica, it is likely such subsequent civil marriages do not give rise to the objective sin of fornication. Alternatively if epikeia / aequitas canonica does not apply, reduced culpability may, as the sinful avoidance of a valid sacramental marriage is not chosen by the parties but is instead imposed by a contingent action of the Church.

Another objection which may be made is that the Church has rejected subjective certainty of nullity as a basis for the reception of Holy Communion by the D&R on a number of occasions, including:

- 1994 CDF Letter at 7 – “The mistaken conviction of a divorced and remarried person that he may receive Holy Communion normally presupposes that personal conscience is considered in the final analysis to be able, on the basis of one’s own convictions, to come to a decision about the existence or absence of a previous marriage and the value of the new union. However, such a position is inadmissable. Marriage, in fact, because it is both the image of the spousal relationship between Christ and his Church as well as the fundamental core and an important factor in the life of civil society, is essentially a public reality”.

- 1998 CDF Memo at 3 b) – “Since marriage has a fundamental public ecclesial character and the axiom applies that nemo iudex in propria causa (no one is judge in his own case), marital cases must be resolved in the external forum … Some theologians are of the opinion that the faithful ought to adhere strictly even in the internal forum to juridical decisions which they believe to be false. Others maintain that exceptions are possible here in the internal forum, because the juridical forum does not deal with norms of divine law, but rather with norms of ecclesiastical law. This question, however, demands further study and clarification. Admittedly, the conditions for asserting an exception would need to be clarified very precisely, in order to avoid arbitrariness and to safeguard the public character of marriage, removing it from subjective decisions”.

Some have suggested, prior to these rejections, the Church had an approved practice in the internal forum (probata praxis Ecclesiae in foro interno) which allowed Holy Communion for the D&R, based on 1973 and 1975 CDF Letters which stated:

“[T]his phrase [probata praxis Ecclesiae] must be understood in the context of traditional moral theology. These couples [Catholics living in irregular marital unions] may be allowed to receive the sacraments on two conditions, that they try to live according to the demands of Christian moral principles and that they receive the sacraments in churches in which they are not known so that they will not create any scandal”.

This however has been disputed, by for example the then Cardinal Ratzinger (now Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI), whom in his 1991 Letter to the Tablet suggested consistent with FC it only applied to those seeking to live in complete continence (i.e. those trying to live in accordance to the demands of Christian moral principles):

“Cardinal Seper’s mention in his letter of 1973 of the “approved practice in the internal forum” … was not referring to the so-called internal forum solution which properly understood concerns a marriage known with certainty to be invalid but which cannot be shown to be such to a marriage tribunal because of a lack of admissible proof. Cardinal Seper for his part was not addressing the question of the validity of a prior marriage, but rather the possibility of allowing persons in a second, invalid marriage to return to the sacraments if, in function of their sincere repentance, they pledge to abstain from sexual relations when there are serious reasons preventing their separation and scandal can be avoided”.

In any event these rejections relate to the treatment of the D&R in the external forum under Canon 915, rather than in the internal forum under Canon 916, and therefore are not relevant to if mortal sin precludes access to the Sacraments.

The application of Canon 915 to all the D&R, regardless of if subjective certainty of nullity exists, is separately considered by this Apologia at 3.0 Public Scandal.

1.5 Sacrament of Penance

The possibility of reduced culpability certainly does not allow ongoing adultery to be absolved, even if venial, as the very factors which reduce culpability for the ongoing sin also make it significantly less likely a person will have the “firm purpose of not sinning for the future … necessary for obtaining the pardon of sins” (Chapter 4 of the 14th Session of the Council of Trent).

However, in relation to the requirement for an individual to confess all relevant sins in order to obtain sacramental absolution as noted by the Second Lateran Council, this is to be understood as all subjective mortal sins rather than all sins. This is shown by:

- Chapter 5 of the 14th Session of the Council of Trent – “For venial sins, whereby we are not excluded from the grace of God, and into which we fall more frequently, although they be rightly and profitably, and without any presumption declared in confession, as the custom of pious persons demonstrates, yet may they be omitted without guilt, and be expiated by many other remedies”.

- CCC 1493 – “One who desires to obtain reconciliation … must confess to a priest all the unconfessed grave sins he remembers after having carefully examined his conscience. The confession of venial faults, without being necessary in itself, is nevertheless strongly recommended by the Church”

- Canon 988 – “A member of the Christian faithful is obliged to confess in kind and number all grave sins committed after baptism and not yet remitted directly through the keys of the Church nor acknowledged in individual confession, of which the person has knowledge after diligent examination of conscience … It is recommended to the Christian faithful that they also confess venial sins”.

- 1996 Letter to Cardinal Baum 4 and 5 (1996) – “Confession must also be complete in the sense that one must tell “all mortal sins”, as was expressly stated in the 14th session, fifth chapter, of the Council of Trent, which explains this necessity not in terms of a simple disciplinary norm of the Church, but as a requirement of divine law, because the Lord established it so in the very institution of the sacrament … It is also self-evident that the accusation of sins must include the serious intention not to commit them again in the future. If this disposition of soul is lacking, there really is no repentance: this is in fact a question of moral evil as such, and so not taking a stance opposed to a possible moral evil would mean not detesting evil, not repenting”.

- 1997 Vademecum at 3.7 – “On the part of the penitent, the sacrament of Reconciliation requires sincere sorrow, a formally complete accusation of mortal sins, and the resolution, with the help of God, not to fall into sin again. In general, it is not necessary for the confessor to investigate concerning sins committed in invincible ignorance of their evil, or due to an inculpable error of judgment. Although these sins are not imputable, they do not cease, however, to be an evil and a disorder”.

Similarly while the Church speaks of absolution requiring “universal” contrition, such that a person who repents must resolve to avoid all sin in the future, this in fact is also limited to subjective mortal sins rather than all sins. As outlined by the Catechism of Pope St Pius X (1908) on the Sacrament of Penance, at q. 51 and 63:

“51 Q: What is meant by saying that sorrow must be universal? A: It means that it must extend to every mortal sin committed …

63 Q: What is meant by a universal resolution [of sinning no more]? A: It means that we should avoid all mortal sins, both those already committed as well as those which we can possibly commit”.

And in the Catechism of the Council of Trent (1566) on the Sacrament of Penance:

“Sorrow For Sin Should Be Universal … The faithful should be earnestly exhorted and admonished to strive to extend their contrition to each mortal sin”.

Therefore:

- Where reduced culpability results in the adultery of the D&R being subjectively venial rather than mortal, it need not be confessed in order for that person to obtain sacramental absolution for any mortal sins of which they may be guilty.

- In accordance the with teaching of the Church prior to AL, it was already possible for some D&R not living in complete continence to be admitted to the Sacrament of Penance.

- The teaching of AL in this regard is not a novelty, and therefore neither contradicts nor even develops the doctrine or sacramental discipline of the Church.

1.6 Sacrament of the Eucharist

In relation to an individual being “conscious of grave sin” in Canon 916, this is to be understood as subjective mortal sin rather than merely objective grave sin, as shown by its predecessor Canon 856 in the 1917 CCL:

“No one burdened by mortal sin on his conscience, no matter how contrite he believes he is, shall approach holy communion without prior sacramental confession; but if there is urgent necessity and a supply of ministers of confession is lacking, he shall first elicit an act of perfect contrition”.

St Thomas Aquinas, in his Commentary on 1 Corinthians 11:27-31 (at 689-696), confirms this is also true of the teaching of St Paul:

“This lack of devotion is sometimes venial … and such lack of devotion, although it impedes the fruit of this sacrament, which is spiritual refreshment, does not make one guilty of the body and blood of the Lord, as the Apostle says here. But a certain lack of devotion is a mortal sin … “But you profane it when you say that the Lord’s table is polluted and its food may be despised …

In a third way someone is said to be unworthy, because he approaches the Eucharist with the intention of sinning mortally”

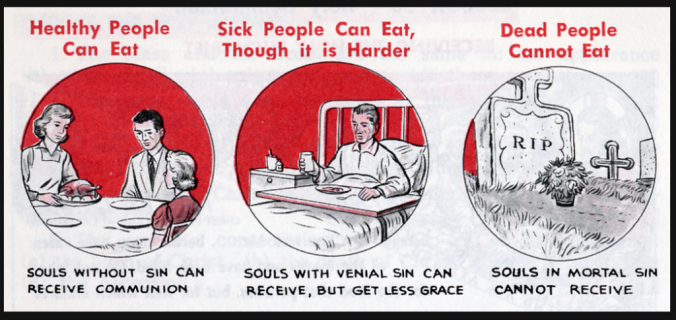

More graphically, this teaching can be seen from the below illustration from an edition of The New Saint Joseph Baltimore Catechism (1969):

The New Saint Joseph Baltimore Catechism (1969)

Therefore:

- Where reduced culpability results in the adultery of the D&R being subjectively venial rather than mortal, it does not preclude their fruitful reception of Holy Communion.

- In accordance the with teaching of the Church prior to AL, it was already possible for some D&R not living in complete continence to be admitted to Holy Communion under Canon 916.

- The teaching of AL in this regard is not a novelty, and therefore neither contradicts nor even develops the doctrine or sacramental discipline of the Church.

1.7 Rarity of Mitigating Circumstances

A further objection which is raised to “pastoral discernment of particular cases” (AL 300) based on reduced culpability, is that while such circumstances exist in theory, they are in practice extremely rare and thus insufficient to justify a case by case approach.

However in order to justify case by case discernment, as opposed to an absolute ban, as formally orthodox it is not necessary to establish that the valid exceptions to the general rule are common. Rather it is only necessary to establish valid exceptions exist, even if they are only rare cases.

Accordingly to the extent it is conceded even that rare cases exist where the D&R lack full knowledge or complete consent, as at least must be conceded based on the precedents of prior pontificates outlined above, then it must also be conceded a case by case discernment is formally orthodox.

A pastoral argument may still be raised against pastoral discernment in this regard, in that in practice access to the Sacraments will not be limited as required to those whom reduced culpability applies. Rather, priests will understand “this possibility as an unrestricted access to the sacraments, or as though any situation might justify it” (the Buenos Aires Directive at Item 7).

However, this argument is merely pastoral rather than doctrinal. Further the force of this pastoral argument is reduced by that fact that in practice abuses of this kind already occur, as noted by RS 83:

“It is certainly best that all who are participating in the celebration of Holy Mass with the necessary dispositions should receive Communion. Nevertheless, it sometimes happens that Christ’s faithful approach the altar as a group indiscriminately. It pertains to the Pastors prudently and firmly to correct such an abuse”.

1.8 Rarity of Mortal Sin

Another and opposite objection which is raised to the idea that “[i]n certain cases” the D&R may be admitted to the Sacraments, is that acknowledging mitigating circumstances exists means that the reality of mortal sin is effectively denied, because they will almost always be available to excuse.

However the error of this objection has been demonstrated by the then Cardinal Ratzinger (now Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI), whom in his 1986 Letter on Homosexuality at 11 states:

“[C]ircumstances may exist, or may have existed in the past, which would reduce or remove the culpability of the individual in a given instance; or other circumstances may increase it. What is at all costs to be avoided is the unfounded and demeaning assumption that the sexual behaviour of homosexual persons is always and totally compulsive and therefore inculpable. What is essential is that the fundamental liberty which characterizes the human person and gives him his dignity be recognized as belonging to the homosexual person as well. As in every conversion from evil, the abandonment of homosexual activity will require a profound collaboration of the individual with God’s liberating grace”.

A similar warning is also provided by Pope St John Paul II in RP 16, which states:

“Sin, in the proper sense, is always a personal act, since it is an act of freedom on the part of an individual person … In not a few cases such external and internal factors may attenuate, to a greater or lesser degree, the person’s freedom and therefore his responsibility and guilt. But it is a truth of faith, also confirmed by our experience and reason, that the human person is free. This truth cannot be disregarded in order to place the blame for individuals’ sins on external factors such as structures, systems or other people. Above all, this would be to deny the person’s dignity and freedom, which are manifested-even though in a negative and disastrous way-also in this responsibility for sin committed”.

Accordingly, it must be remembered the mere existence of mitigating factors in a concrete situation, does not mean they are sufficient to mitigate a sin from mortal to venial. As outlined by CCC 1858, “[t]he gravity of sins is more or less great”, and thus lesser mitigating factors can merely distinguish between more and less serious mortal sins.

AL does not provide guidance on what circumstances might be sufficient to reduce culpability for objectively grave sin so that it is not subjectively mortal, on the basis that (AL 304):

“At the same time, it must be said that, precisely for that reason, what is part of a practical discernment in particular circumstances cannot be elevated to the level of a rule. That would not only lead to an intolerable casuistry, but would endanger the very values which must be preserved with special care”.

Accordingly the discernment of when mitigating factors are sufficient to reduce culpability are in the first instance the responsibility of an individual in conscience, guided by their pastor, rather than any human third party (AL 37):

“We also find it hard to make room for the consciences of the faithful, who very often respond as best they can to the Gospel amid their limitations, and are capable of carrying out their own discernment in complex situations. We have been called to form consciences, not to replace them”.

However, while as AL 308 notes the “Gospel itself tells us not to judge or condemn (cf. Mt 7:1; Lk 6:37)”, equally as the Dubia rightly states:

“However, conscience does not decide about good and evil … The proper act of conscience is to judge and not to decide. It says, “This is good.” “This is bad.” This goodness or badness does not depend on it. It acknowledges and recognizes the goodness or badness of an action, and for doing so, that is, for judging, conscience needs criteria; it is inherently dependent on truth”.

Therefore, all such judgments of conscience are subject to the particular and final judgements of Christ, at which time as CCC 1039 outlines:

“In the presence of Christ, who is Truth itself, the truth of each man’s relationship with God will be laid bare. The Last Judgment will reveal even to its furthest consequences the good each person has done or failed to do during his earthly life”.

Scott,

First of all, congratulations for the hard work involved in your Apologia. It takes a great effort to summarize your thesis in such a comprehensive way.

As you´ll see, I have many objections to your Apologia. I’ll comment on each one separately, although it´ll take me some time. The way you structured your Apologia makes discussing it much easier.

In regards to 1.0 Mortal Sin:

1.3. You correctly present the well established doctrine regarding the POSSIBILITY of reduced culpability due to lack of knowledge and/or full consent. I don’t think the Dubia or any worthy criticism of AL have denied this.

However, you fail to prove something that is foundational to your thesis: that the possibility of reduced culpability due to lack of deliberate consent can be applied prospectively (future sins) once ignorance no longer exists (which will quickly be the case of d&r in process of discernment with priest). How do you reconcile this with martyrdom and the extreme duress they go through? We´ve all seen horrible images of how Christians are executed by ISIS militants because of their faith. Don’t they have a much better excuse to break the moral law when they face death as result of keeping God’s commandments? They too have children and wives to take care of, I assume!

According to St. John Paul II, “To maintain that situations exist in which it is not, de facto, possible for the spouses to be faithful to all the requirements of the truth of conjugal love is equivalent to forgetting this event of grace which characterizes the New Covenant: the grace of the Holy Spirit makes possible that which is not possible to man, left solely to his own powers.” (John Paul II, Christian vocation of spouses may demand even heroism, 17 September 1983).

As you point out in CCC 1859:

“Mortal sin requires full knowledge and complete consent. It presupposes knowledge of the sinful character of the act, of its opposition to God’s law. It also implies a consent sufficiently deliberate to be a personal choice. Feigned ignorance and hardness of heart do not diminish, but rather increase, the voluntary character of a sin.”

What matters here is if there’s consent enough to consider the act a free choice. Circumstances only diminish culpability if they render the choice involuntary. For example, we’re talking about something one does while sleeping, under involuntary effect of drugs, pathological disorder that, sudden life threat or other external pressure that results in a reflex or involuntary action, etc. It has never been Church’s teaching to excuse sin, let alone intrinsically evil sin, after weighing alternatives in conscience, no matter how difficult their consequences may be at the human level. I think you completely misunderstood this point.

Why does AL suggests that further sin may come from choosing to live in continence, in accordance with the Gospel? Isn’t that evil a consequence of the previous sinful decision to remarry and have children with someone that is not your spouse, rather than a consequence of doing the right thing, i.e. separation or continence? If AL is saying that in order to do good to your children and second “spouse” one must do an intrinsically evil act, then it is saying that the end justifies the means.

1.4. I don’t understand why you conclude from FC84 and the text from St. Thomas Aquinas that subjective conviction of nullity reduces culpability due to ignorance. What do you mean by ignorance due to nullity? What are they ignorant of? One thing is to be convinced of the nullity and not be able to prove it, and so one may not be culpable for divorce or separation, and another thing is to decide that because of that certainty one can get civilly married again even if the Church prohibits so.

When JPII says in FC84 that these persons need special attention and accompaniment he refers to the fact that, even if they wanted to fix their irregular situation after their conversion, they can’t do so because of lack of evidence, so they are specially suffering and the Church needs to help them. It has nothing to do with reduced culpability when they remarried or they continue to live as husband and wife. Even if they were not culpable for the divorce, there is no circumstance that justifies the decision to commit adultery, assuming there is no ignorance of the moral norm and she is not forced to do it against her will. That´s all that counts. Fear for the wellbeing of the children is not an excuse, it actually is a mortal sin in itself if the result is “shunning what ought not to be shunned according to reason”, as Thomas Aquinas teaches in ST II-II, Question 125, Articles 3.

Therefore, if out of fear for the future of the children, she decides to do what her conscience recognizes as mortal sin, she is culpable of two mortal sins, inordinate fear and adultery. So as you can see it works the opposite way once you have a formed conscience, and martyrs are witnesses of that. Hard teaching, no doubt about that!

Now, it could be that her fear is so extreme that it becomes almost pathological and renders her act involuntary, in which case it could reduce the culpability. But as you can see, this is in retrospective, at the spur of the moment. Because if you tell me that God put me in a situation in which there is no possible way to avoid mortal sin and my actions are morally neutral because I cannot use my free will, I would most probably despair and begin to think that maybe Christ didn’t die for me after all, and Grace apparently is not sufficient in my case.

1.5. You say that “In accordance the with teaching of the Church prior to AL, it was already possible for some D&R not living in complete continence to be admitted to the Sacrament of Penance.”

I don´t think that´s true in the way you mean it, because as I said, couples that are well informed cannot possibly claim venial sin in a permanent sinful situation. Only couples that have made a firm purpose to amend their lives and live in continence but, due to their weakness, they fall again, can be admitted to the Sacrament of Penance. You have not provided any magisterial document that says that they can be absolved without a purpose of amendment.

1.6. Similar comment as in 1.5. They have never been admitted to the Sacraments without firm purpose of amendment. It it were the case that, in a retrospective basis, they were subject to such duress or passion that their free will was diminished, then they obviously would be fine as per Canon 916, but never admitted to Communion due to Canon 915.

1.7. As you say, traditional moral theology teaches that there are mitigating factors that could reduce or eliminate culpability. But the way you seem to understand it (prospectively) cannot be found in the Magisterium, and it certainly was not St. Thomas Aquinas thinking.

Finally, Church´s mission is, among other things, to take care of souls and guide them to heaven. That´s the framework for any legit pastoral. I´m not sure why you see as orthodox a pastoral that you admit will do much harm to souls. Pastoral and doctrine are not independent, an idea that some people have successfully advanced in the Church. A bad pastoral that goes against the mission of the Church is in itself a sort of doctrinal error. Don´t you think?

Thanks for your time.

LikeLike

Jorge,

Thank you for your response. Trying to take your points in order, my thoughts are as follows:

1. Prospective Application of Reduced Culpability – I think on this point you may be conflating limits on intellect (i.e. full knowledge), with limits on will (i.e. complete consent).

To take the example of martyrdom, I would indeed affirm this is an example where mitigating factors can make a sin in a sense involuntary by impairing the will. While I know denying Christ is intrinsically evil, and indeed that martyrdom is the demand of the Gospel, the duress / coercion of a gun to the head might make it very difficult for me to actually do the right thing. In this case I still sin, but I think all would agree the coercion means my sin would be less than voluntary, and thus my guilt is reduced. This is confirmed by CCC 1754, which explicitly confirms a fear of death can reduce culpability for an evil action.

2. St. John Paul II on Heroism – That is a relevant quote. I will include it in my Section 2.4, where I deal with the idea avoiding adultery is “impossible”.

3. Voluntary and involuntary acts – I deal with this question in my 2.3 Consequences as Mitigating Circumstances, with reference to Aquinas, including the James Bond example raised by the Dubia. I’m not sure if you have had a chance to get that far – If you have please do let me know any defects your find in that analysis.

4. Further Sin – I could have sworn I had covered that in the Apologia, but it appears to have fallen out at some point. I will rectify that shortly.

In any event, based on the clarifications by the Pope (rejecting situational ethics) and his spokesman Fr. Antonio Spadaro (rejecting adultery could be a moral duty), I think this must be understood as “consequences as mitigating circumstances”, rather than “ends justifies the intrinsically evil means”.

That this logic is indeed the intent of AL, can be seen in the text of AL301, which places the idea of “further sin” firmly in the context of an example of mitigating factors. This is why AL301 is headed “mitigating factors”, and the reference to “further sin” is bookended by references to subjective factors which limit the ability to make a decision. Similarly in Fr. Antonio Spadaro interview with Crux we find the same context – “recognition that, in a particular case, there are limitations which attenuate responsibility and guilt – particularly where a person believes they would fall into a worse error, and harm the children of the new union”.

While needing clarifications is less than ideal, if one supports the dubia submitted by the four Cardinals, they must be accepted. It would be radically inconsistent to request clarification of an ambiguous text, and then reject the validity of the clarification on the basis it was not consistent with one’s own preferred reading of the ambiguity.

5. Subjective conviction of nullity and ignorance – The ignorance in this case is in relation to whom one is married. While St Thomas holds we can’t be inculpably ignorance that adultery is wrong, he equally allows that we could be ignorant of whom is our spouse. So if you were sure of nullity, but wrong, you could be inculpably ignorant of the fact you are actually married. I will clarify this in the text of the Apologia.

6. Inordinate fear – St Thomas certainly considers inordinate fear can be a further mortal sin. But as noted in my 2.3 Consequences as Mitigating Circumstances, he also recognises “necessity resulting from coercion” as rendering acts only partly voluntary (De Malo q. 2, a. 2).

Indeed, as I noted at my 2.4 The Commandments and Impossibility, I think Dante best express the space which exists between the shinning light of the martyrs and mortal sin. Those who were forced to break vows still dwell in heaven, but only the lowest sphere, as “If their will had been unbroken, like that which kept Lawrence on the grid and made Mucius stern to his own hand, then, as soon as they were free, it would have driven them back on the path from which they had been dragged; but will so firm is rare indeed”.

7. Impossibility – I deal with this question in my 2.4 The Commandments and Impossibility. Again, I’m not sure if you have had a chance to get that far – If you have please do let me know any defects your find in that analysis.

8. Sacrament of Penance – I specifically deny anyone can be absolved for a sin without a purpose of amendment. My argument is that if reduced culpability applies, so the adultery is venial, it is not required to be confessed (per Trent etc).

As to being well informed, again I would point to subjective certainty of nullity as an ignorance which could not always be cured. Further there are mitigating factors which don’t rely upon a lack of knowledge.

9. Canon 915 – In this section I am merely dealing with Canon 916. I deal with Canon 915 in my 3.0 Public Scandal.

10. Pastoral vs Doctrinal – I am partial to the idea pastoral mistakes must somehow be caused by, or represent, a doctrinal error (I also like the idea every schism is caused by a heresy somehow). However if we look to the history of the Church, that would mean it has constantly been heretical! Pastoral errors by the Church are a constant – In every era you consider they will be found.

So ultimately I think we have to accept that while Jesus promised his Church would not teach error, he also promised that like all men those who represent it would sin. It was not for nothing St. John Paul II is said to have made official public apologies for over 100 such wrongdoings (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_apologies_made_by_Pope_John_Paul_II).

LikeLike

Scott, I really don’t get what argument you are trying to construct with the “ignorance of nullity” stuff. For example:

5. Subjective conviction of nullity and ignorance – The ignorance in this case is in relation to whom one is married. While St Thomas holds we can’t be inculpably ignorance that adultery is wrong, he equally allows that we could be ignorant of whom is our spouse. So if you were sure of nullity, but wrong, you could be inculpably ignorant of the fact you are actually married

Anne could apparently get married in the Church, and then have it turn out to be no marriage (null) because something hidden from you was an impediment to marriage – say, Bill was acting under some compulsion (such as a shotgun being held by your father under his coat). But that’s not what we are talking about, here, are we? Suppose rather that the marriage falls apart, and they get divorce, and Anne applies for an annulment on a basis that SHE knows (from personal observation) is true, but she cannot prove. So though she is “subjectively certain” that the marriage is null, she cannot get the formal decree of nullity because of lack of admissible evidence. OK, is THAT the scenario?

But nothing demands that she go and try to marry Sam. The Church is telling her “we have not annulled your marriage, you are still considered married in the public forum, you are not free to marry.” So she IS FREE to not marry again. If she attempts to marry again, she cannot marry Sam in the Church, because the Church refuses to consider her free to marry. So if she marries him at all, she marries him outside canonical form, i.e. without the Church’s blessing, and this “marriage” CANNOT be valid. Even if she knows for certain that her first marriage is null, the marriage with Sam cannot be valid. So, how is she ignorant of who she is married to? She isn’t married to Bill, and she isn’t married to Sam, and she knows both perfectly well. Even if, say (to add complications), Sam had been married before, and had a divorce, and “married” Anne outside the Church, and THEN Sam got an annulment from his first marriage, even so, Anne knows that her “marriage” to Sam is not valid because it was outside the Church. This is part of the reason for demanding canonical form in order to even have a valid marriage to begin with.

St. Thomas’s example of a person who “didn’t know who they were married to” and thus committed adultery was quite a different story. In the days of arranged marriage, where Bill may not even meet his chosen bride until the day of the wedding, he may be unsure of her looks (what with veils and all). Suppose that he marries Anne, but Anne’s sister Barbara kidnaps Anne and replaces her in the bridal chamber. Bill has relations with Barbara because “he doesn’t know he isn’t married to her” (she is, after all, a sister and looks and sounds alike to the inexperienced eye and ear). This is a case of mistake, error, about which person is here that is presenting herself as Bill’s wife Anne. He is NOT in error about (a) whether he is married, or (b) the formal identity of the person he is married to, Anne, or (c) whether it is right for him to have relations with his wife Anne. The “object of the act” which Bill wills is “to have relations with my wife Anne” , which is not disordered at all, nor morally in doubt. The act he engages in is materially that of adultery, but not formally, his error is inadvertend, and there is no guilt at all for Bill.

But how can you use this for a case of nullity, even of a person who is “subjectively certain a first marriage is null, for which the evidence is inadmissible.” I don’t see how you can get a case of “ignorance of who she is married to” out of that in a way that makes her inculpable for a second civil marriage that was not celebrated under canonical form, or makes her unaware the second marriage is null also.

LikeLike

If the “subjective certainty of nullity” about the first marriage were IN ERROR, it still doesn’t cause a problem. If the conditions which precipitated a divorce (at least in this country tribunals don’t take cases for annulment until the divorce occurs) has separated them, she is not living with Bill, and is subjectively certain she should not be living with him. Not a moral difficulty. If she is subjectively certain the first marriage (to Bill) is valid but she is wrong, after the divorce she can continue to consider herself married to Bill in absentia and honor her marriage vows from a distance, and there is no moral problem. I don’t see how to construct a case where her subjective certainty creates a true difficulty, EXCEPT if she ignores Church discipline and attempts a second marriage without canonical form (i.e. without a DECREE of nullity and the second marriage blessed by the Church). And, of course, in that case the second marriage is invalid no matter what the condition of the first marriage is, objectively or subjectively.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tony,

I had passed over the problems of canonical form, because in that regard I want to make a further reform proposal, and didn’t what to confuse the issue at hand.

However, you are correct that canonical form as provided for in Canon 1108, means that where a Catholic marries civilly it is made to be invalid (not just illicit) even if they are in God’s eyes free to marry. Accordingly, for those “subjectively certainty of nullity” who remarry, all it means is that their objective sin is fornication rather than adultery.

However, this invalidity is not a doctrinal requirement, as shown by the fact its application is limited to Catholics by Canon 1117 (i.e. the civil marriages of baptised non-Catholics can be valid). Accordingly, my further reform proposal would be that Canon 1108 be reformed such that lack of canonical form only creates a presumption of invalidity (i.e. it does not get the benefit of Canon 1060), rather than imposing invalidity absolutely.

In the absence of such reform, the question of the culpability for the fornication follows the same principles as for adultery, being is the fornication done with full consent. In this regard, given the sin arises because the person can’t validly marry despite the fact they should be free to do so, I would think it could be said full consent is lacking.

That is to say it is the Church, not the person or divine law, which is making marriage impossible. The person doesn’t consent to this sinful avoidance of marriage, it is forced on them externally and absolutely.

LikeLike

“A person who is conscious of grave sin is not to … receive the body of the Lord without previous sacramental confession”.

Canon 916 says grave sin and not mortal sin, so why is this being read as if it says mortal? All acts of adultery are grave sins, though it’s possible that a sin that is grave is not necessarily a mortal if full knowedge and full consent are lacking.

If someone has enough knowledge to claim invincible ignorance of an action they plan on repeating, how can it be said they have invincible ignorance? And if they are lacking full consent, are they being held in a second marriage against their will? Isn’t any sex act where consent lacking rape?

LikeLike

In terms of grave sin vs mortal sin, I outline why Canon 916 must be understood this way at 1.6 Sacrament of the Eucharist.

As it was put by Canonist Patrick Travers:

“Canon 916 is addressed directly to those who are considering the reception of the Holy Eucharist. It states that they may not normally do so if they are “conscious of grave sin” (conscius… peccati gravis). Here, the interpretation of “grave sin” as a synonym for mortal sin, with all of its subjective elements, appears to be the only one possible.”

LikeLike

In terms of a lack of full consent, there are examples of duress which fall short of rape as understood in civil law. For example, if a man threatened to financially abandon a women and her children to serious poverty, in the event continence was proposed.

LikeLike

Accordingly, my further reform proposal would be that Canon 1108 be reformed such that lack of canonical form only creates a presumption of invalidity (i.e. it does not get the benefit of Canon 1060), rather than imposing invalidity absolutely.

Scott, I have myself suggest a similar modification of the Canon Law. Since it seems to be Church law rather than natural law that blocks a Catholic from marrying outside the Church, the Church could change that. And if SO MANY people are falling into this difficulty, maybe the preponderance of goods vs evils would be better served by a more relaxed law about the validity of a Catholic’s civil marriage.

But it would create VAST new problems in sorting out those Catholics who divorce and remarry again civilly, and then again. In fact, having only the presumption would generate far more cases of people who are subjectively certain (of either validity or nullity) and yet unable to prove it sufficiently for a decisive declaration? So, let me ask this: what if the law were changed to provide that a civil marriage between Christians is valid? Assuming that the civil marriage retained the formulas needed to elicit consent to the real notion of marriage, not the newer mock-up versions, or worse yet the self-made nonsense that isn’t even recognizable as a contract much less a marital one. I recognize the difficulties that will be created by borderline vows, so assume for the moment that civil authorities allow you to use the form of vows supplied by your church to contract a civil marriage. But retain the notion that a first marriage is assumed valid and the assumption can only be defeated with a decree of nullity. Given that, it would remain true that a D&R who did not get an annulment would ALWAYS be certain that their SECOND marriage is invalid, regardless whether the first was or not.

I don’t think you answered my difficulty above at all, about how subjective certainty about nullity (in either direction) creates any problems for a D&R to follow the absolute norms regarding continence.

LikeLike

I suppose I am thinking of the problem with fornication as not a lack of continence, which isn’t required of them by divine law, but a failure to get validly married (which is). In this perspective, impossibility applies, because the Church makes it impossible to be validly married (despite not needing to make it so).

LikeLike

So, I may have missed something in the argument, and I hope I don’t cross territory already covered in the excellent comments, but I fail to see how you have established a case that a couple who are not husband and wife can continue to live together more uxorio without that being adultery of fornication proper (ie, as some venial rather than mortal sin).

To quote St Thomas here on their mortal nature:

“It is heretical to say that fornication is not a mortal sin. Adultery and fornication are forbidden for a number of reasons. First of all, because they destroy the soul…” Commentary on the Ten Commandments, 6

And here on deliberate reason:

“Since a moral act takes its species from deliberate reason, the result is that by such a subtraction the species of the act is destroyed.” Summa I-II, Q88A6

The subtraction of deliberate reason is possibility, but is incompatible with a functioning household over time–which is explicitly what is being defended by AL (“a second union consolidated over time…”). Without deliberate reason one could hardly (to quote Twelfth Night):

“…sway her house, command her followers,

Take and give back affairs and their dispatch

With such a smooth, discreet and stable bearing

As I perceive she does.”

For the mortal sin of adultery (or fornication) to be changed into a merely venial sin, deliberate reason must be subtracted. How do you explain that deliberate reason can be subtracted for a prolonged period of time, and even over both parties! (Presumably both, not just one, can receive communion.)

Some overmastering emotion alone cannot account for that, and it would not cover the intention to continue to live and even build a certain kind of life into the future, which is precisely a choice of the deliberate reason.

I do not think you have succeeded in showing how this is even possible in theory. If you succeed, isn’t it at the cost of declaring the moral capacity of those you are arguing for below what is called for to perform properly human acts?

And even after all of that, if you succeeded in showing how one might live a life of adultery that was not really adultery, but was merely a kind of venial adultery, you bounce off the fact that the Church cannot justify even venial sin.

Card. Newman’s words on the subject could hardly be stronger:

“The Catholic Church holds it better for the sun and moon to drop from heaven, for the earth to fail, and for all the many millions on it to die of starvation in extremest agony, as far as temporal affliction goes, than that one soul, I will not say, should be lost, but should commit one single venial sin, should tell one wilful untruth, or should steal one poor farthing without excuse.”

But to quote from VS81 (a section you bold):

“Consequently, circumstances or intentions can never transform an act intrinsically evil by virtue of its object into an act “subjectively” good or defensible as a choice.”

If adultery is indefensible as a single act, how can it be approved as a mode or state of life that I can choose to live out, which is certainly the case if AL303 is correct “that it is what God himself is asking amid the concrete complexity of one’s limits.”

I am skipping over ignorance, as that was well addressed in the comments already, and also be because AL stipulates that one can “know full well the rule”.

So, in brief summary, I do not think you have shown how a couple can choose to live a life committing sinful acts which are mortal in their genus without ever consenting to those acts.

LikeLike

ThomasL,

Thank you for your comments, which are also excellent and thoughtful.

The place I am starting from is that the Church, before Francis, already acknowledged the objectively grave sin of adultery may not be subjectively mortal sin. This occurred, as I note in the Apologia, in the 2000 PCLT Declaration.

In terms of how complete consent can be limited over extended periods, again I think the precedents I have adduced show that the Church before Francis also accepted this could arise. Duress, fear, habit, inordinate attachments, and other psychological or social factors etc are not things which last a moment, nor are they things which completely eliminate our ability to function in society.

In terms of justifying venial sin, I don’t believe AL is guilty of that error. If the objectively grave disorders were justified, they could not be called sin even venially, but instead could be morally right actions.

This is actually the point Cardinal Newman and VS are making in those quotes – Venial sin is sin, not something we accept as good or defensible. That venial sin does not preclude receiving Holy Communion, as has also been the constant teaching of the Church, does not change that it remains an evil.

In terms of the “what God himself is asking” portion of AL, I address that in my 2.0 Intrinsic Evil. In that section of my Apologia, I show this must be understood as a breaking open of the law of gradualness, and cannot be seen as a gradualness of the law or situationalism.

LikeLike

@Scott,

I remain unconvinced that you have demonstrated how “complete consent can be limited over extended periods.”

I think you have only done so by raising the bar on what is required for consent such that anything but wholeheartedness is not sufficient.

The testimony of the martyrs rebukes this, and moreover your perspective would in effect remove both martyrdom and apostasy from moral responsibility if either was attended by duress or fear: if the apostate is not responsible for his choice to apostatize because his consent is less than complete for fear, neither is the martyr responsible for his choice to remain steadfast despite his own fear. You can only excuse the apostate of sin by snatching the crown off the head of the martyr.

Even more than the one act, it would excuse the apostate to continue to live his life in apostasy, not just offering the single pinch of incense, but a lifetime of offerings to false gods, so long as the threat of martyrdom hangs over him.

Is this really what the Church has always an everywhere taught? Or has it rather taught, as in VS91, that “In raising [martyrs] to the honour of the altars, the Church has canonized their witness and declared the truth of their judgment, according to which the love of God entails the obligation to respect his commandments, even in the most dire of circumstances, and the refusal to betray those commandments, even for the sake of saving one’s own life.”

I can hardly improve on Tony’s and Jorge’s comments in section 2.0 though on duress, fear, and habit, so I would only direct you back to them.

LikeLike

ThomasL,

Again, I think you take a more rigorist line than the Church has though out the ages. Who would doubt those threatened with martyrdom, and lie in respect of their faith in Christ, have done so with less than complete consent? The evil is intrinsic and grave, yet it cannot be said the act was fully voluntarily.

And yet given what you yourself have quoted from Cardinal Newman, who could doubt we are still called to avoid that venial sin even undo death, so as to receive the Crown? Because while renouncing Christ would not be fully voluntarily, yet it is not fully involuntarily, and can be resisted.

The commandments of God are not impossible with Grace. But nor are we fully guilty for every grave sin committed. This is the teaching of the Church regarding the difference between grave and mortal sins, which has been the case long before Pope Francis.

LikeLike

I do not think I, or any of your commenters, have denied that the culpability for an objectively grave act could never be less than mortal. I referenced Summa I-II Q88A6 earlier, but it is nice to quote again:

“A sin which is generically mortal, can become venial by reason of the imperfection of the act, because then it does not completely fulfil the conditions of a moral act, since it is not a deliberate, but a sudden act, as is evident from what we have said above. This happens by a kind of subtraction, namely, of deliberate reason. And since a moral act takes its species from deliberate reason, the result is that by such a subtraction the species of the act is destroyed.”

That could also happen by ignorance (culpable or inculpable) which he addresses in one of the objections.

But your arguments seem to read as if any duress, or any fear, etc. was sufficient to “not completely fulfil the conditions of a moral act,” and further, that that can be applied not just to actions in the past, but prospectively to actions not yet committed, but preemptively mitigated, since one can in fact be living indefinitely in a state where, while still able to order life generally, one remains unable to “completely fulfil the conditions of a moral act.”

I do not think that can be deduced from the teaching above, or anywhere else in the teachings of the Church.

To continue the apostate example above, if suddenly confronted, or suddenly seized by fear, the very suddenness or power might excuse to a degree as St Thomas describes above, because deliberate reason was subtracted, and so the species of the act changed. But if one had time to think in their cell and deliberately chose to offer incense, having thought it over, that would not be excused under traditional moral theology. If you think it would, I would invite you to find a single text from the Magisterium supporting it. The case was certainly a common enough one for much of Early Church history.

By your arguments regarding duress and complete consent, it goes further than the one act though, I do not see how you can escape from the conclusion that the Christian, continually threatened with martyrdom, is not only able to offer incense once, but to choose a life of public apostasy for as long as the threat of persecution remains without ever gravely sinning.

Is that accurate? If not can you describe why not?

This seems quite analogous to living a life of adultery as long as some threat of hardship is associated with stopping, and so is not off topic.

LikeLike

ThomasL,

It seems to me we might have been sucked into a tangent that is, perhaps, not strictly required. Perhaps if we step back for a moment to the bigger picture.

The formal orthodoxy of AL does not hinge on precisely where we draw the line between mortal sin, and reduced culpability rendering a sin venial. As I note in my section 1.7, AL cannot be shown to be in error, simply because while cases of reduced culpability exist in theory they may be in practice extremely rare. All that is required to justify case by case discernment as orthodox, as opposed to an absolute ban, is that valid exceptions exist even if very rare.

On the other side in my section 1.8, I equally warn against any tendance to act as if any duress or fear is sufficient to reduce culpability (using Cardinal Ratzinger’s warning in his 1986 Letter on Homosexuality).

So if we both accept reduced culpability exists, and the 2000 PCLT Declaration binds us to understand it may also exist in relation to the D&R, then at a high level I think my case for the orthodoxy of AL is made out (at least in relation to mortal sin and Holy Communion).

But that being said, in terms of your argument in respect of fear / duress only excusing when it overwhelms in the moment, my argument against this based on Aquinas can be found in my section 2.3 Consequences as Mitigating Circumstances.

Further, in terms of your example regarding martyrdom or offering incense, I would start with Reconciliatio et Paenitentia 17:

“With the whole tradition of the church, we call mortal sin the act by which man freely and consciously rejects God, his law, the covenant of love that God offers … This can occur in a direct and formal way in the sins of idolatry, apostasy and atheism … It is a mortal sin, that is, an act which gravely offends God and ends in turning against man himself with a dark and powerful force of destruction”.

Thus we can see that even apostasy must be done freely in order to be mortal sin. If we then turn to Fr. Thomas Slater’s 1925 “A Manual of Moral Theology for English-Speaking Countries”, we find at page 17:

“Inasmuch as bad actions done through fear are simply voluntary, it would follow that they are imputable to the agent, so that fear does not excuse him from sin. And this is true of such actions as are intrinsically bad and against the natural law. The Church has always considered those to be apostates who through fear of death or persecution deny their faith, though less culpable than those who renounce it without excuse (Can. 2205)”.

In this regard Canon 2205 of the 1917 Code, now included as Canon 1324, provides:

“If, however, the act is intrinsically evil, or involves contempt of faith or of ecclesiastical authority, or the harm of souls, the circumstances spoken of in the preceding paragraph do indeed diminish the responsibility but do not take it away.

Therefore I think we can affirm, with the Church, that culpability is reduced for denying Christ through fear of death or persecution.

LikeLike

I am not aware of any moral theologian ever that has not said that motive, or duress, or emotion might reduce voluntariness to a degree.

However it seems to me in your response that you are reading “reduced” as if it always and everywhere means “changed from mortal to venial” which is not warranted.

Not all mortal sins are equally evil, though all entail a turning away from God. As St Thomas said, already quoted, but needs re-re-quoted, “a moral act takes its species from deliberate reason, the result is that by such a subtraction the species of the act is destroyed.”